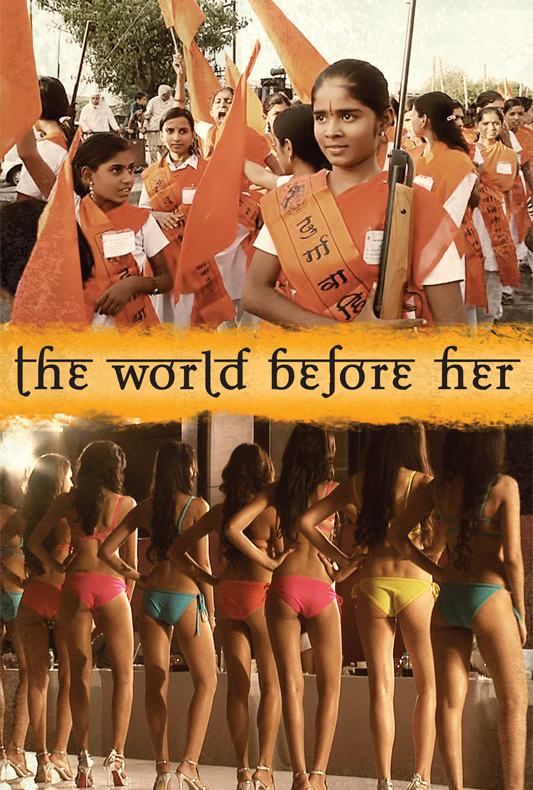

Film review: ‘The World Before Her’

Note: Spoiler alert, if you have not watched the film

Nisha Pahuja’s film ‘The World Before Her’ tries to trace the diametrically opposite journeys of two groups of young women in India viz. contestants of the Ms. India beauty pageant and the trainees of Durga Vahini, a right wing women’s training unit of the Vishwa Hindu Parishad.

As the film navigates through the aspirations and beliefs of many such young women, it takes a closer peek at the lives of Ruhi Singh and Prachi Trivedi who come from very contrasting socio-cultural milieu. While Ruhi is a 19 year old contestant competing with my other girls for the tiara of the Ms. India beauty pageant, Prachi is a 24 year old trainer at the Durga Vahini camp and is by her own submission, a die-hard stickler.

The film quickly meanders between the worlds of glamour and Hindutva to give us an intimate view of both. One gets to observe the strong assimilationist tendencies of both the Hindu fundamentalist movement and the fashion industry. While on one side, young girls are being fed with religious intolerance and are being trained in martial arts on the pretext of self defence and Hindu ethos only to uphold patriarchy and Hindu supremacy; the other world makes the commodification of women’s bodies stark and total.

The notion of objectification comes clearly to the fore when Sabira Merchant proudly likens the models in the pageant to finished products on an assembly line in a factory. Dehumanization and visual dissection of body parts of women attains an even higher and a newer orbit when the models are paraded like scarecrows shrouded in white burkha-like cloaks for the judges to evaluate ‘just the legs’.

The film may have done its best to raise curtains over both the realms of modelling and religious fanaticism but does end up offering a very binary and a polarised view of the choices ahead of the young women in India. Sabira Merchant’s binary juxtaposition of the ‘old and the new worlds’ as the only two destinations ahead is a case in point here as it tends to ignore the wide spectrum of other choices and possibilities.

The film is brilliant when it uncovers the dark underbelly of the Hindutva discourse by revealing its inherent islamophobia and contempt for Christianity and Christian evangelists. Adolescent Chinmayee’s firm resolve to shun friendship with Muslims and Christians denudes the dangerously high levels of indoctrination of some vulnerable Indian youth.

It is interesting to note how two young women have different takes on the same issue of female infanticide. Both Pooja Chopra, a Ms. India 2009 and Prachi Trivedi speak of it, although with contrasting views. While Prachi is raised and moralized to be rather grateful to her father for the great favour of letting her stay alive despite her being a girl child; Pooja is enormously thankful to her mother for separating from her violent husband i.e. Pooja’s father, to save Pooja from female infanticide. Prachi’s understanding of terrorism as being limited to the use of ammunition and her legitimization of vigilante justice yet again unmasks a lopsided value system carefully handed down by belligerent Hindutva supremacists.

Nisha Pahuja does a exceptionally brilliant job of holding up a mirror to show how religion is used to interpret filial duties (of a daughter) only to perpetuate the patriarchal paradigm and to promote a unitarian concept of a Hindu state to the point of extermination of all other faiths.

The film does well in laying bare the deeply entrenched stigma in the minds of some fashion wannabes in the industry. Gurpreet’s bigoted and flagrantly homophobic response to Fardeen Khan on being asked how she’d respond to her son being gay only shows how deeply rooted homophobia is in our society and how even the fashion industry that claims to be equal and inclusive is no exception.

Also, Shweta’s overarching views on Americanization and the urbane, as she tries to build a case to label the rising urban Indian middle class as largely progressive are very telling. We are able to view the level of indoctrination that deftly invisibilises the subaltern. Ruhi’s sense of self at 19 and of her future ahead that according to her allows her freedom only for another 4-5 years unveils the underlying culture of subordination that operate of out age old patriarchal postulates.

It is only very reflective of a largely prevalent mind set among many girls like Ruhi, who are caught between the cross hairs of westernization and patriarchy and struggle to make their best possible choices within the patriarchal stranglehold. All this is made possible with skilful editing that zig zags between both the worlds to arrest the attention of the viewers while bringing out important issues.

The film portrays all its characters i.e. both the beauty pageant contestants and the girls at the Durga Vahini camp as real people of strengths, inadequacies, insecurities and fears. Their views are not sensationalized and the film offers responsible and sensitive access to their lives and does justice to them.

In short, the film appears to be an intimately rich narrative of the private worlds of SOME young women in India pursuing paths chosen by them through highly blinkered and insular frames of reference.

One Comment