The Right to Privacy: The Promise for full Recognition of Transgender Rights

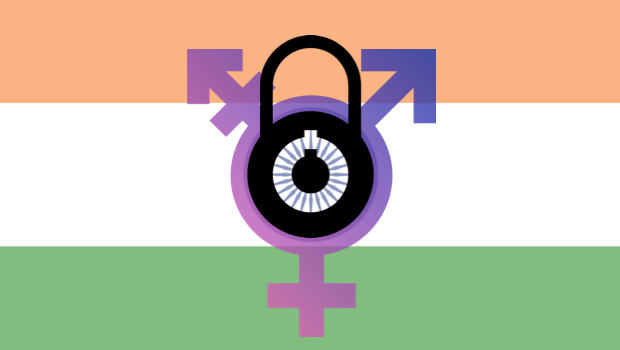

When petitions against Aadhaar were filed in the Supreme Court 5 years ago, little did any one think that these cases would have such a huge impact on the rights of sexual minorities in India. The judgment has completely altered the landscape for the recognition of the right to sexual orientation and gender identity and I argue in this piece that the broad contours of the rights encompassed within the framework of privacy given by the Supreme Court paves the way for full recognition of the rights specifically of the transgender community.

When petitions against Aadhaar were filed in the Supreme Court 5 years ago, little did any one think that these cases would have such a huge impact on the rights of sexual minorities in India. The judgment has completely altered the landscape for the recognition of the right to sexual orientation and gender identity and I argue in this piece that the broad contours of the rights encompassed within the framework of privacy given by the Supreme Court paves the way for full recognition of the rights specifically of the transgender community.

Although the decision was unanimous, there were six separate concurring judgments. A common thread runs across the findings given in all judgments that while the right to privacy is rooted in the right to life and liberty under Article 21, it is also enshrined in all other fundamental rights, including the right to equality and the fundamental freedoms under Article 19 of the constitution. It unanimously overruled the right judge decision in MP Sharma v. Satish Chandra to the extent that it holds that it indicates that there is no right to privacy and also overruled Kharak Singh v. State of UP to the extent that it did not give a positive finding on the right to privacy.

I would like to focus this piece on the manner in which the right to dignity has been the focus for the Court for the development of the right to privacy. This argument has special significance for the guarantee and protection of the rights of the transgender community. That the right to live with dignity includes the right to autonomy, to make decisions about one’s life choices was eloquently affirmed by Justice Dhananjay Chandrachud where he holds, “ …The best decisions on how life should be lived are entrusted to the individual. ……The duty of the state is to safeguard the ability to take decisions – the autonomy of the individual – and not to dictate those decisions.” He went on to hold that dignity permeates the core of the rights guaranteed to the individual under Part III of the constitution and privacy assures dignity to the individual.

Privacy ensures that a human being can lead a life of dignity by securing a person from unwanted intrusion. In the context of dignity, specific references to the protection of one’s sexuality, sexual orientation and gender identity were made as being part of one’s intimate life choices that need to be protected under the rubric of privacy. Justice Chandrachud went as far as to hold that the reasoning of the Supreme Court in Suresh Koushal vs. Naz Foundation and Others that only a miniscule minority was affected was flawed and held “That “a miniscule fraction of the country’s population constitutes lesbians, gays, bisexuals or transgenders” (as observed in the judgment of this Court) is not a sustainable basis to deny the right to privacy. The purpose of elevating certain rights to the stature of guaranteed fundamental rights is to insulate their exercise from the disdain of majorities, whether legislative or popular. The guarantee of constitutional rights does not depend upon their exercise being favourably regarded by majoritarian opinion. The test of popular acceptance does not furnish a valid basis to disregard rights, which are conferred with the sanctity of constitutional protection. Discrete and insular minorities face grave dangers of discrimination for the simple reason that their views, beliefs or way of life does not accord with the ‘mainstream’. Yet in a democratic Constitution founded on the rule of law, their rights are as sacred as those conferred on other citizens to protect their freedoms and liberties.”

The Court went on to hold that sexual orientation is an essential attribute of privacy and that the right to privacy and the protection of sexual orientation lies at the core of the fundamental rights guaranteed by Articles 14, 15 and 21 of the Constitution. This settles the rights for the setting aside of Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code. Sexual orientation rights, sexual orientation is not limited to the gay, lesbian and bisexual groups but inextricably linked to transgender and intersex persons as well. Not limiting the recognition of the right to sexual orientation, the Court went on to hold that “The rights of the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender population are real rights founded on sound constitutional doctrine. They inhere in the right to life. They dwell in privacy and dignity. They constitute the essence of liberty and freedom. Sexual orientation is an essential component of identity.” It held that “Equal protection demands protection of the identity of every individual without discrimination.” This would most certainly include the right to one’s self-identified gender identity as upheld as an integral part of the right to life in NALSA v. Union of India.

The Court also held that the prosecutions under Section 377 while they may be only in a few cases, such acts of hostile discrimination are constitutionally impermissible because of the chilling effect which they have on the exercise of the fundamental rights and held that merely because there may have been a low number of prosecutions cannot mean that there was no violation of rights. The chilling effect of criminal law that violates the rights of the trans community is particularly relevant not only in the context of Section 377 but in the context of other criminal laws as well. Section 36A of the Karnataka Police Act, which has now been amended, and the Telangana Eunuchs Act are examples of criminal laws which have been targeting the trans community. While there may not be many prosecutions under such laws, they are used as threats by the police to permeate fear and violence among the community. For the first time this chilling effect faced by sexual minorities has been recognized. What is fascinating is the manner in which not only Justice Chandrachud’s main judgement, but many of the separate judgements referred to the right to gender identity and other rights relating to one’s intimate life in an very outspoken manner. J. Bobde held that the right to privacy is confined not only to intimate spaces such as the bedroom or the washroom but goes with a person wherever he or she is. It is interesting that these issues have been addressed by the courts because washrooms and toilets are the sites were current battles for recognition of the rights of the trans communities are being fought and could pave the way for the future.

How is Privacy defined?

Privacy has been defined quite simply as the right to be let alone. An elaboration of privacy has been defined by the Court as the autonomy of the individual to make his or her personal life choices. It held that the notion of privacy enables the individual to assert his / her / their personality. Justice Nariman gives three parts to the this right – (i) the aspect of privacy that relates to the physical body, such as interference with a person’s right to move freely, surveillance of a person’s movements etc., (ii) informational privacy relating a person’s private information and materials and (iii) the privacy of choice which includes the rights and freedom to make choices of one’s most intimate and personal choices. This third prong of privacy would relate to the intersection between one’s mental and bodily integrity and entitles the individual to freedom of thought, belief and self-determination and includes the right to determine one’s gender identity. Family, marriage, procreation and sexual orientation are all integral to the dignity of the individual and the fundamental freedoms under Article 19 entitled an individual to decide upon his or her preferences. Read in conjunction with Article 21, liberty enables the individual to make choices on all aspects of life including what to eat, how to dress, or what faith to follow. What I found most relevant and moving was the observation of Justice Nariman that the guarantee of privacy as a fundamental right was important as it would protect it, despite the shifting sands of the majority government in power. It would protect non-majoritarian views, diversity and plurality which is so crucial to our country, especially in present times where we are witnessing such intolerance of differences.

Interestingly, it was also held that privacy has both positive and negative content. Not only does the right to privacy restrain the state from committing an intrusion upon the life and personal liberty of a citizen, it also imposes a positive obligation on the state to take all necessary measures to protect the privacy of the individual.

The Horizontal application of the Right to Privacy:

Justice Kaul is the only judge who refers to the protection of the right against non-state actors. He held that there is an unprecedented need for regulation regarding the extent to which such information can be stored, processed and used by non-state actors in addition to the need for protection of such information from the State. Privacy is a fundamental right, which protects the inner sphere of the individual from interference from both State, and non-State actors and allows the individuals to make autonomous life choices. This is particularly an important issue facing the trans community as they face a serious amount of violence at the hands of private actors – family members, employers, neighbours and the society that discriminates against them on the basis of their gender identity. This is a huge step and the development of the right to privacy against private persons needs to be developed judicially.

Conclusion and Learnings:

While we should celebrate and savour the gains of at this far-reaching judgement, what the learnings? As a women’s rights and transgender rights activist and lawyer, I find this judgement points out the need for the gender rights movements to align with other social movements and the interconnectedness of rights. The privacy rights battle in the context of Aadhaar was a battle that the LGBT movement and the women’s rights movement had not engaged with. We are incredibly fortunate that we had a Court that rose unanimously in favour of declaring proudly the rights to sexual orientation and gender identity but this should only strengthen our resolve to work for the protection of rights across movements, of class, gender, caste, disability and religion if we want to strive to protect diversity and difference.