wide open spaces

The road meanders southwards for a distance. Then, it cuts west relentlessly until it finds the coast. It has taken me two hours to get from the fringes of the choking metropolis to the wide open spaces.

I’ve travelled down this road with an old friend in the back seat, high as a kite, strumming his guitar, hoarse from singing for two hours straight.“I’ve seen the needle and the damage done,” he sang, as he fought his own chemical demons, careening wildly between brilliance and stupor.

I’ve travelled down this road with a newer friend, his bag of naked cassette tapes in my lap. Honeymoon with Hedon, he said to me, a month after we met, and I followed him into his dream, marshalling his tapes as he drove laconically through the night. I pass the bus shelter where we stopped to buy cigarettes. I remember the way he looked at me out of the corner of his eye as he started the car. He’s the one, I remember thinking at the time.

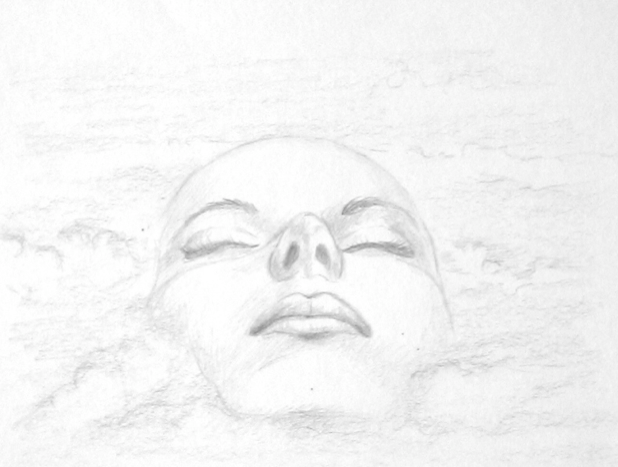

The last time I was on this road, I was with her. I say “her” because I am unable to name our relationship. We have known each other since childhood. She had just lost her mother, and I, my family. We were driving down this road, going round in circles; trying to make sense of it all, concluding that it wasn’t supposed to make sense, and starting over. We had driven up a steep incline, in quiet desperation, and as we caught our breath on an outcrop that overlooks the valley, we looked down at this very road, and the railway track that ran alongside it, for the longest time. In an effervescent moment, we fell into a fragile, quasi-incestuous, fiercely passionate togetherness that consumed itself, and us, for the best part of a decade.

That decade is now past, and for the first time, I am alone on this road that I know so intimately. I’m in a little white car. The headlights forge an ephemeral path through the rain that by now has begun to seem eternal. One of the wipers is worn; every time it completes its arc across the windshield, it sounds remarkably like human flatulence. Somehow, that makes me feel a little less unsettled.

I never thought I would do this, or that I could do this. On the face of it, it’s rather a simple thing to do. Pack an overnight bag. Buy petrol. Drive. Alone.

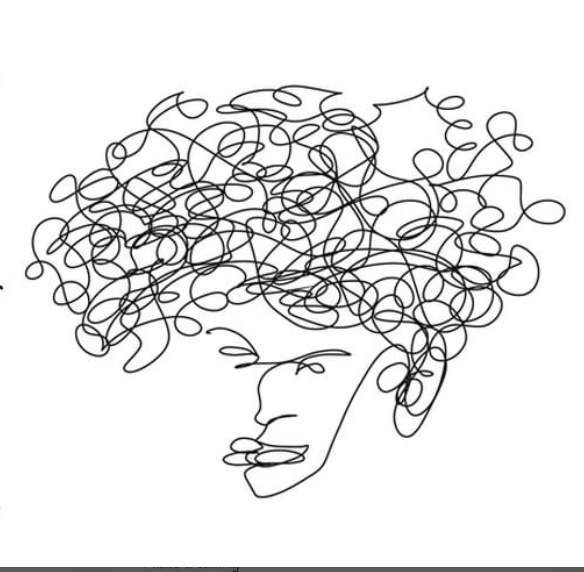

When I drive by myself, in the city, I relish this space, this privacy, this cocoon that travels with me. This room that is my own. No one can see me. No one can put me in a neatly labelled box and leave me there to languish till the end of time. I can see everything that surrounds me. The glacial lanes of traffic. The houses, now ramshackle, now opulent. People spilling out of windows and balconies, doorways and shopfronts, footpaths and buses. The sea of humanity evokes in me a strange sense of alienation, like a long lost giant family that won’t have me. I put them in neatly labelled boxes, to make sense of it all. Men. Women. Children. Cows. Dogs. Ruffians. Friends. Lovers. Flibbertigibbets. Sweet revenge. I can’t hear their protest, because, in my mind, solitude has a soundtrack.

Like a barbed wire fence,

Strung tight, strung tense,

Prickling with pretence,

This borderline.

I feel powerful; in control of the little table-top model of the city I live in. The table-top model of a city that I now am fleeing.

I’ve spent the past month preparing for this flight.

In the beginning, I just forced myself to stay awake through the night, smoking, drinking coffee, binge-watching old television shows off the internet with the volume turned all the way down, until I heard the first birds announcing the imminent explosion of the mundane. By the end of the first week, it was as if I had travelled to another part of the world, where night was day, and day was night. When I began to feel truly nocturnal, I ventured out into the spaces inhabited by other nocturnals. The bus terminal. The university. The zones where desperate creatures of the night, not very much unlike me, flag down cars much like the the one I was driving and haggle at the window before climbing into the passenger seat.

I did this every night, with a thermos full of coffee and a pack of cigarettes for company, until I was no longer afraid of the night, or of the ghouls it engenders. Bring on the night, I sang as I drove home at dawn; I couldn’t stand another hour of daylight.

I paid off the milkman. I emptied out my refrigerator. I bought granola bars and bags of crisps, an ice box, toilet paper and a blue raincoat. I told a friend, over coffee, that I was going away, indefinitely. She said I was crazy. I said it was time. She said she wished she could change my mind. I knew she didn’t mean that, and I was relieved. We both wept; tears of recognition and despair. I wondered, when we parted, if I was going to see her again. Don’t be dramatic, said a familiar voice in my head.

Now, the evening by my coffee table seems like a distant memory. All the trappings of the life I had been living are now behind me. An unnameable fear lurks just beyond the reach of my feeble headlights as I drive through the darkness, and I am suddenly consumed by the banal. If something horrible were to befall me on this journey, and if I were to cease to exist, would anyone notice that I was gone?

“We’re alone, each one of us,” he of the bagful of naked cassette tapes told me once, in an intimate embrace that had seemed familiar at the time. He said it in the kindest, gentlest tone of voice, but inside of me, paroxysms of grief broke through the afterglow. “Let’s not talk of love or chains, of things we can’t untie,” he sang, an imitation of Leonard Cohen that was both tawdry and unimaginably affectionate. His withdrawal left in me a throbbing, sentient void that refuses to die. Enough strangeness and melancholy to last a lifetime, the void says, when I ask why. I ask often.

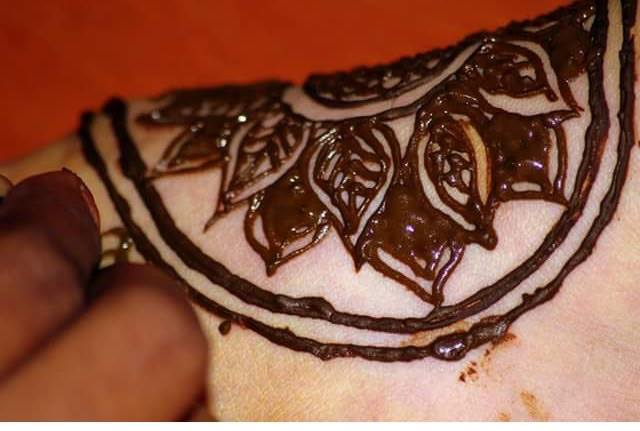

I have since given away all his Cohen albums, but I can still smell him on my skin, taste him in my mouth, feel the contours of his ribcage against mine. The affection in his voice is more real than it was at the time. It’s as if I’m back in that moment, and now, after so many years, I finally understand what it was that he was trying to say to me, and I feel strangely recalcitrant. I grudge the moment its very existence, because it draws me into an unforgiving hierarchy of sublime moments that proscribe my own identity.

So, I drive, away from the sublime, away from the familiar, and into the lightening western horizon.